A Study of GST Levy on Sugar Sweetened Beverages

INTRODUCTION

Sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) have been identified as a major source of sugar content leading to obesity and related health complications. The World Health Organization (WHO) discourages the consumption of sugar since it contributes to unhealthy weight.[1] There is an increasing global trend to combat the ill effects of such sugar consumption by a mix of policy interventions, of which the tax on SSBs is a prominent fiscal policy intervention.[2]

The proposal to tax SSBs is an evidence-based public health policy intervention championed by organizations like WHO, World Bank and the World Federation of Public Health Associations Non-Communicable Diseases Prevention & Health Promotion and Policy Working Group.[3]

The crux of the matter is that the consumption of sugar has to be reduced, the industry should be nudged towards reformulation of product offerings so that healthier alternatives are developed and consequently, the public health risks associated with unhealthy dietary habits are minimized.[4] However, as with any policy intervention, an erroneous understanding of the policy philosophy could lead to a botched up design, making way for undesired second-order effects and unintended outcomes on implementation.[5]

In the interest of appreciating the philosophy of SSB taxation as an evidence-based public health policy intervention, this white paper clarifies and simplifies the ideas and rationales for the imposition of a SSB tax, discusses international best practices, highlights the issues in the existing tax structures in India and suggests possible methods to make the intervention far more targeted and effective so that the tax regime can keep in mind the heaflth quotient of young India, particularly when it is estimated that 65% of Indians are below the age of 35.

PHILOSOPHY OF SSB TAXATION

The Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases (NCDs) was rolled out by the WHO in 2013. The primary objective was to to combat obesity and diet related NCDs.[6] The action plan identified four key risk factors for NCDs –

- tobacco

- harmful use of alcohol

- unhealthy diet and

- physical inactivity.[7]

As part of reducing modifiable risk factors for diseases and underlying social determinants through creation of health-promoting environments, WHO inter alia recommended eliminating industrial trans-fats through the development of legislation to ban their use in the food chain and reducing sugar consumption through various measures including effective taxation on SSBs.[8]

What are SSBs and why target them explicitly?

SSBs are defined by WHO as “all types of beverages containing free sugars, and these include carbonated or non-carbonated soft drinks, fruit / vegetable juices and drinks, liquid and powder concentrates, flavored water, energy and sports drinks, ready-to-drink tea, ready-to-drink coffee and flavored milk drinks”.[9]

WHO notes that SSBs are a major cause of obesity, and hence recommends that adults and children reduce their consumption of sugar to less than 10% of their daily energy intake (equivalent to roughly 12 teaspoons of table sugar for adults with a diet of 2000 kcal, and 9 teaspoons for children with a diet of 1500 kcal).

The WHO manual categorises beverages in the Harmonized System according to content of sugar and non-sugar sweeteners as follows:

Table 1 Categories of beverages in the Harmonized System according to content of sugar

| Sugar Sweetened Beverages (SSB) | Beverages with non-sugar sweeteners | Beverages that are not sweetened |

| 22.02

Waters, including mineral waters and aerated waters, containing added sugar and other sweetening matter or flavored |

22.01

Waters, including natural or artificial mineral waters and aerated waters, not containing added sugar or other sweetening matter not flavored; ice and snow |

|

| 20.09

Fruit juices (including grape must) and vegetable juices, unfermented and not containing added spirit, whether or not containing added sugar or other sweetening matter |

||

| 04.02

Milk and cream; concentrated or containing added sugar or other sweetening matter |

04.01

Milk and cream; not concentrated, not containing added sugar or other sweetening matter |

|

| 04.03

Buttermilk, curdled milk and cream, yoghurt, kephir, fermented or acidified milk or cream |

||

| 04.04

Whey and products consisting of natural milk constituents |

||

| 18.06

Chocolate and other food preparations containing cocoa |

21.01

Extracts, essences, concentrates of coffee, tea or mate; preparations with a basis of these products; roasted chicory |

21.06

Food preparations not elsewhere specified or included |

Source: WHO Manual on Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Taxation Policies to Promote Healthy Diets, 2022

It is essential to note that SSBs include a diverse set of products with added sugar ranging from aerated water to yoghurt to chocolate preparations. Similarly aerated water without added sugar is excluded from the category of SSB.

Given that SSBs tend to contain more sugar than the WHO recommendation, there are both public health and economic rationales to target them explicitly via taxation. The core of these rationales is enumerated below –

a. Public Health Rationale

- Leading sources of sugar, and contain little-to-no added nutritional value;

- Individuals who consume SSBs do not compensate for the added calories by eating less food, which leads to weight gain and obesity;

- Epidemiological studies suggest that added sugars in liquid form, such as SSBs, may pose greater health risks, including the risk of metabolic syndrome, compared to sugar-containing solid foods.

b. Economic Rationale

- Overconsumption occurs because the full cost of consumption is not accounted for in the market price (i.e., internalities and negative externalities are present)

- Negative externalities include lost productivity and the financial costs of treating diseases associated with SSB consumption in countries where health care is publicly funded. The market price consumers pay for SSBs does not reflect this true cost to society and results in overconsumption of SSBs from a societal perspective.

- Internalities – Full long-term cost is discounted by consumers in favour of immediate gratification.

The essential point to appreciate is that the intake of sugar must be discouraged and SSBs are not the only source of sugar. In the pursuit of discouraging the consumption of SSBs, policy must be careful not to end up encouraging the consumption of sugar from other sources. Therefore, policymakers should understand that taxing SSBs is not the end game. But it is only the first step in the battle against unhealthy dietary practices.

How to overcome the public health risk posed by SSBs?

The steps suggested by WHO to reduce the public health risk posed by SSBs are[10] –

- Fiscal measures such as taxation on SSBs

- SSB taxes increase their price, which in turn makes SSBs less affordable and decreases consumption.

- Countries may also structure taxes on SSBs to encourage reformulation and decrease sugar content in the overall portfolio of beverages.

- Recommendations on the marketing of foods and non-alcoholic beverages to children to reduce the exposure and the power of marketing of foods high in salt, sugar and fat,

- Implementing a standardized labelling system including interpretive front-of-pack labelling,

- Public education of both adults and children for literacy about food and creating a healthy food environment around schools.

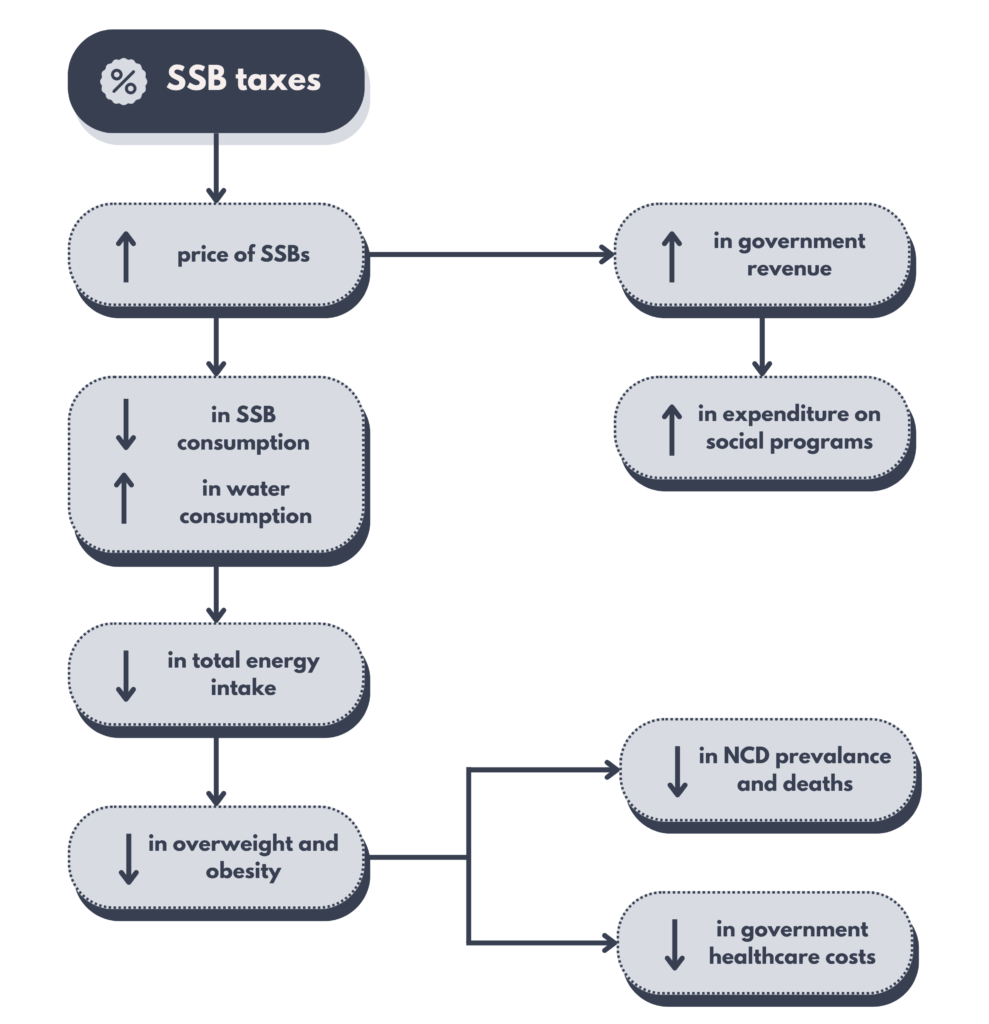

How are SSB taxes expected to work?

Figure 1. How SSB taxes are expected to work?[11]

Figure 1. How SSB taxes are expected to work?[11]

The policy-mix approach of WHO

The policy suggestions offered by WHO are not stand-alone suggestions, but a holistic “policy mix”. A policy mix implies a focus on the interactions and interdependencies between different policies as they affect the extent to which intended policy outcomes are achieved. Research suggests that policies in isolation might fail to have the intended effect and a policy mix is more likely to achieve the intended objective.[12] Research also suggests that a universally applicable policy mix is difficult to design, and both the form of the policy instruments and the implementation context have to be factored in to make a policy mix more likely to achieve the intended effect.[13]

It is important to understand why the policy-mix approach advocated by WHO has to be holistically implemented rather than a piece-meal approach. The holistic nature of policy intervention is essential on three fronts. One, all the suggested policy instruments have to be implemented together. Two, all products which contain sugar and contribute to obesity and diseases should be subject to the said policy mix intervention. Three, the intervention has to be specifically targeted at SSBs and not be diluted by taxing non-sugary drinks too under this intervention.

Let us first understand why the policy instruments must be holistically implemented instead of implementing them in isolation. Increasing taxes on SSBs is a demand side burden which could adversely effect the supply side of the industry like reduction in investment and employment unless there is a balancing supply side intervention or demand side opportunity as well. When the guidelines recommended by WHO are holistically implemented, it works towards a better understanding of the ill-effects of SSBs and leads to consumer demand for reformulated sugar-free healthy product offerings across the industry thus rejuvenating innovation in the industry leading to increased investment and employment.

In essence, taxation of SSBs is made more effective when implemented as part of a comprehensive policy package (what policy scholars call “policy mix”) that also includes other demand reduction measures such as the restriction of marketing of SSBs; regulation of their labels, for example to include warnings; banning the use of health claims, as well as other persuasive elements such as images of fresh and natural foods, cartoon characters; banning SSBs from schools and other settings; as well as providing education about healthy dietary practices and awareness about unhealthy diet choices.[14]

Let us next understand why it is essential to subject all products which satisfy the definition of SSBs to such policy intervention. Each of these products is a source of sugar and contributes to the increased likelihood of obesity. If sugared carbonated soft drinks are taxed but sugared energy drinks are not taxed, then the consumer preference is likely to lean towards sugared energy drink which is also a SSB, thereby defeating the purpose of the policy.[15]

Further, let us understand why it is important that the recommendations of WHO be targeted specifically at SSBs. A non-targeted taxation policy fails to clearly distinguish between SSBs and non-SSBs (such as plain, unsweetened water, milk, teas and non-sugary beverages). Targeted taxes exempt unsweetened beverages or apply taxes to unsweetened beverages at a lower rate than SSBs. The failure to make this crucial distinction derails the primary objective of imposing such taxes and non-targeted taxation regimes run the risk of being less effective at shifting consumption behaviour toward healthier substitutes since public awareness and reaction gets mixed up.[16]

INTERNATIONAL PRACTICE

The Nordic countries of Denmark, Finland and Norway were supposedly the first countries to introduce taxes on SSBs for revenue purposes in the 1920s-1930s. The first health-related taxes, over and above extant taxes on other foods and beverages, were imposed in the early 2000s in several Pacific Island nations (French Polynesia, Nauru, and Samoa), followed by European experiments in 2010s.[17]

The tipping point in taxing SSBs was the imposition of a targeted excise tax by Mexico in 2014. With an explicitly stated aim of addressing the country´s high obesity/NCD burden, this taxation move was hoped to ease the health burden of the country with the highest obesity and SSB consumption rates in the world.[18] Since then many countries have imposed SSB tax in different forms.

One important feature of SSB tax internationally is that it is largely a targeted tax (i.e., the tax clearly identifies products with added sugar and differentiates such products from non-sugared versions by imposing higher tax rate on the sugared version vis-à-vis the non-sugared version). This is especially true of the European and Central Asian Region. Whereas some of the non-European jurisdictions have implemented a SSB tax which is poorly targeted and therefore less effective.[19] Some illustrative case studies of targeted SSB tax are discussed below.

In United Kingdom, a “leviable drink” is explicitly defined as one which satisfies all of the following conditions –

- It has had sugar added during production, or anything (other than fruit juice, vegetable juice and milk) that contains sugar, such as honey;

- It contains at least 5 grams (g) of sugar per 100 millilitres (ml) in its ready to drink or diluted form;

- It is either ready to drink, or to be drunk it must be diluted with water, mixed with crushed ice or processed to make crushed ice, mixed with carbon dioxide, or a combination of these;

- It is bottled, canned or otherwise packaged so it’s ready to drink or be diluted and (v) it has a content of 1.2% alcohol by volume (ABV) or less.[20]

The definition clearly notes that there must be a minimum amount of sugar in the drink for it to be leviable to the Soft Drink Industry Levy.

In Finland, in the case of (i) aerated water, (ii) non-alcoholic beverages and (iii) fermented beverages, a clear distinction is made in terms of the sugar-free and sugared versions of these products. The sugar-free versions are taxed at half the rate at which the sugared versions are taxed.[21]

In Ireland, the ready to consume drinks are liable to Sugar Sweetened Drinks Tax (SSDT) if they satisfy three criteria – (a) They are classified within particular headings of the Combined Nomenclature (CN) of the European Union. The relevant headings, CN 2009 and CN 2202, cover juices and water and/or juice-based drinks, (b) they contain added sugar and (c) the total sugar content of the drink must be five grams or more per 100 milliliters.[22]

In Canada, SSB tax applies to –

- sugar sweetened ready-to-drink beverages such as soft-drinks, fruit flavoured drinks, sports and energy drinks;

- sugar sweetened dispensed beverages such as soda fountain drinks, slush drinks and fruit juices, and

- sugar sweetened concentrated drink mixtures.

It does not apply to –

- 100 per cent natural fruit or vegetable juices;

- sugar-free sodas;

- chocolate milk;

- alcoholic beverages;

- syrups, purées, and powders used primarily as a cooking or food preparation ingredient and

- beverages prepared for the customer in a food and/or beverage-service establishment at the time of purchase (e.g. adding sugar to coffee or tea). Therefore, in effect, “products to which a sugar-based ingredient has not been added by the manufacturer” are not subject to the SSB tax.[23]

In France, a flat rate SSB tax of $0.24 per litre is levied if added sugar is more than 11g /100mL on soft drinks, fruit beverages, vitamin water, flavoured milk, and non-alcoholic beverages with artificial sweeteners. In essence, the primary taxing criteria is the presence of added sugar.[24]

In Hungary, the Public Health Product Tax is an excise levy applied on the salt, sugar, and caffeine content of pre-packaged foods for which there are healthy alternatives. Here, the tax bracket is much wider and taxed products include sugar-sweetened beverages, energy drinks, confectionery, salted snacks, condiments, stock cubes, flavoured alcohol, and fruit jams.[25] But still the target on sugar content and differentiation between sugared and non-sugared versions is a crucial feature of the taxation design in this case.

In Mexico, a volumetric SSB tax of 1 peso per litre has been imposed on all non-alcoholic drinks with added sugar.[26]

In Belgium, since 2016, a volumetric excise tax is being imposed on all non-alcoholic beverages which are either sugar sweetened or sweetened through other sweeteners. Whereas “aerated waters, not containing added sugar or other sweetening matter nor flavoured” are zero-rated under this taxation policy.[27]

While a flat rate of tax is imposed in some countries, there are a good many tax jurisdictions where a tiered tax structure is implemented in proportion to the sugar content in the beverage. The table below presents some cases clearly endorsing the WHO thinking of-

- more sugar – more taxes

- less sugar-less taxes

- no sugar-no taxes.

Table 2. Tax rate proportional to sugar content across different jurisdictions

| Sl No | Country | Sugar content | Tax rate |

| 1 | Ireland | 5 – 8 grams/100 mL | €16.26 per hectolitre |

| > 8 grams/100 mL | €24.39 per hectolitre | ||

| 2 | Chile | < 6.25gm/100ml of sugar | 10% ad valorem tax |

| > 6.25gm/100ml of sugar | 18% ad valorem tax | ||

| 3 | Colombia | <6g/100ml | Non-taxable |

| 6g – 10g of sugar/100ml | COP 18 | ||

| > 10g of sugar/100ml | COP 35 | ||

| 4 | United Kingdom | 5-8g added sugar/100ml | ₤0.18/litre |

| > 8g added sugar/100ml | ₤0.24/litre | ||

| 5 | Estonia | 5 – 8 grams/100 mL | 10 cents per litre |

| > 8 grams/100 mL | 30 cents per litre | ||

| 6 | France | >11g/100ml | $0.24 per litre |

| 7 | Latvia | <8g/100ml | €0.074 per litre |

| >8g/100ml | €0.14 per litre | ||

| 8 | Thailand | 6-8gm/100mL | 0.10 baht/litre |

| 8-10gm/100mL | 0.30 baht/litre | ||

| 10-14gm/100mL | 0.50 baht/litre | ||

| >14g/100mL | 1 baht/litre | ||

| 9 | USA: City of Boulder, Colorado | >5gm/12 fluid ounces | 2 cents/ounce |

| 10 | Spain, Catalonia region | 5 – 8 grams/100 mL | €0.08/litre |

| > 8 grams/100 mL | €0.12/litre | ||

| 11 | Portugal | <80g/litre | €0.08 |

| >80gm/litre. | €0.16 | ||

| 12 | Poland | <5g/100ml | 0.50 PLN |

| >5g/100ml | 0.05 PLN | ||

| 13 | Brunei | SSBs with more than 6gm/100mL total sugar | 0.40 Brunei dollars/litre |

| Soy milk drinks with >7gm/100mL total sugar | |||

| Malted or chocolate drinks with >8gm/100mL total sugar | |||

| Coffee based or flavoured drinks with ≥6gm/100mL. | |||

| 14 | Mauritius | For Every gram of sugar | 6 cents/gram sugar |

| 15 | Peru | >6g/100ml | 25% |

| 16 | South Africa | >4g/100ml | 2.1 cents/gm sugar |

| 17 | St Helena | >5g/litre | £0.75 per litre |

| 18 | Malaysia | carbonated, flavored, & other non-alcoholic drinks with sugar content above 5 g per 100 mL or on fruit or vegetable juices with sugar content greater than 12 g per 100 mL | RM 0.40 per L |

It is an international practice to specifically exempt those products that are not to be subjected to the SSB tax depending on the consumption pattern, culture and context of the country or jurisdiction. This is best borne out in the cities of USA where such taxes are implemented.

In Albany CA, beverages distributed from retailers with revenue <$100,000 per year are exempted.[28]

In Berkeley, CA, distribution tax of 1 cent per ounce on non-alcoholic sweetened drinks is imposed. However, items not containing sugar such as dairy and meal-replacement drinks, diet sodas, and 100% juices are explicitly exempted.[29]

In Oakland, CA: SSB tax was implemented in 2017. SSB distribution tax of 1 cent per ounce on non-alcoholic drinks with added caloric sweetener is imposed. Dairy drinks, 100% juices; beverages distributed from retailers with revenue <$100,000 per year are exempted.[30]

In San Francisco, CA, 100% juices, artificially sweetened beverages, infant formula, milk products, and medical drinks are exempted.[31]

In Seattle WA, diet sodas, milk-based drinks, & 100% fruit juice are exempted.[32]

The global experience does not equivocally uphold the economic efficacy of the SSB taxes. Global evidence is at best mixed on how efficient taxing SSBs is on reducing their consumption and nudging reformulation leaning towards healthier options.[33] It is also argued that such a taxation regime places disproportionate burden on the poor.[34] Further, it is argued that these taxes do not necessarily reduce health inequalities or reduce the consumption in the long run.[35] However, a lot more research is needed to evaluate the efficacy and long term impact of these taxes before a conclusive assessment of the same can be made.

INDIAN SCENARIO

In the current Indian context, the policy environment around discouraging SSB consumption suffers from an erroneous understanding and lack of deeper appreciation of the policy mix advocated by WHO. The specific problems are discussed in the paragraphs that follow.

In India, the taxation on SSBs has been given effect to based on the recommendation of the committee report on the Revenue Neutral Rate and Structure of Rates for the Goods and Services Tax, 2015. The report fails to adequately appreciate the WHO guidelines where the focus is to tax “beverages containing free sugars”. Instead, the report recommended sin tax on demerit goods and listed “luxury cars, aerated beverages, paan masala, and tobacco and tobacco products” as demerit goods.[36] Consequently, all aerated beverages are taxed at 28% GST + 12% compensation cess leading to a total of 40% tax in India.[37] Therefore, the target of the SSB tax in India is misplaced at aerated drinks rather than sugared drinks.

The tax base in India is narrowly targeted at aerated drinks whereas the focus on sugar content as per WHO guidelines is absent. Therefore, a lot of products which satisfy the definition of SSBs as per WHO guidelines have been left out of the ambit of SSB tax in India. Since the taxable entry reads as “aerated drinks” in the Indian context, SSBs like “Milk and cream; concentrated or containing added sugar or other sweetening matter” are not subjected to the compensation cess that “aerated drinks are subject to”. Consequently, products like “aerated waters, not containing added sugar” which are explicitly categorised as non-SSBs globally are wrongly subject to SSB tax in India. This is violative of the cardinal principles of tax design – equity and efficiency of the tax.

One of the objectives of the policy mix advocated by WHO is to nudge the industry towards reformulation of their product offerings so as to make them healthier. However, the SSB taxation approach in India without adequate attention to other factors like the indifference towards the costs to the industry and the small-scale retailers dependent on the sale of such beverages can have adverse effects on the industry as a whole and discourage the flow of investments into the industry in India. It can also decimate the sugar industry in India, which is one of the largest producers of sugar in the world. Appropriate consideration needs to be given to such effects of a taxation policy.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Clear distinction between aerated beverages and sugar sweetened beverages

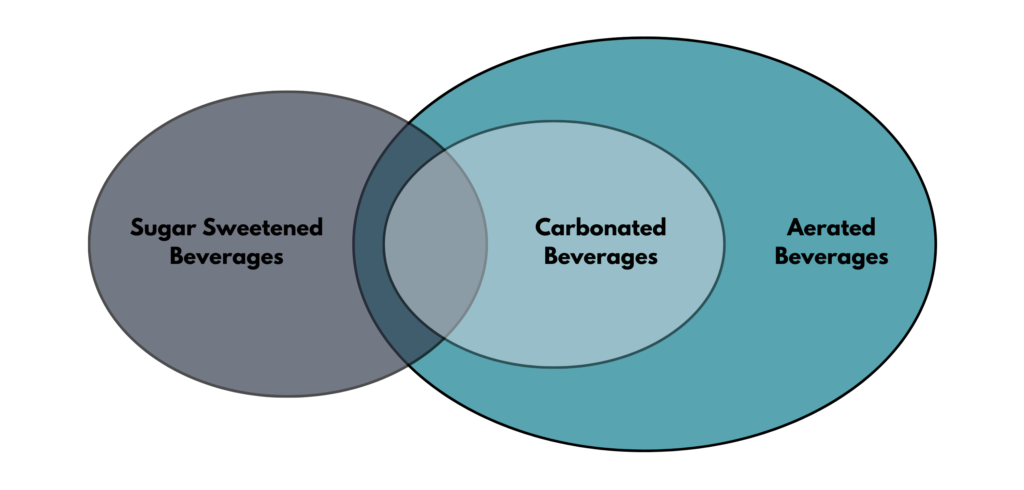

- Aeration/Carbonation of beverages is a process of addition of carbon dioxide/other gases to a beverage under pressure. Aeration is a broader term encompassing addition of any gas whereas carbonation is specific to the addition of carbon dioxide. In essence, carbonated beverages are a subset of aerated beverages.

- Aeration is intended to achieve one or more of three primary objectives –

-

- Getting the beverage to sparkle;

- Giving the beverage a tangy taste and

- Preventing the beverage from spoilage since the carbon dioxide eliminates oxygen thereby preventing bacterial growth.

Nothing in the whole process suggests addition of sugar content to the beverage. No evidence suggests that carbonated or sparkling water is bad for health. There are reports which suggest that aerated drinks may have positive health effects like reducing cardiovascular risk[38], decreasing satiety and improving dyspepsia, constipation and gallbladder emptying[39], and positive sensory perceptions[40]. Scientific authorities, including the US Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) and Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JEFCA), have analysed the independent research available on carbon dioxide and verified that it is safe.[41]

Further, aerated/carbonated beverages can be sweetened by addition of sugar or sweeteners or can be non-sweetened, non-sugary too. Therefore, it is essential to appreciate that carbonated beverages do not necessarily mean sugar sweetened beverages. Figure-2 below captures the distinction succinctly.

Figure 2. Aerated, Carbonated and Sugar Sweetened Beverages

Figure 2. Aerated, Carbonated and Sugar Sweetened Beverages

At present, all aerated waters, containing added sugar or other sweetening matter or flavoured, attract 28% GST plus 12% cess irrespective of sugar content. However, it would be a prudent tax measure that aerated water, i.e. ordinary potable water charged with carbon dioxide under pressure, be classified under heading 22.01, and imposed GST at 18% and excluded specifically from the levy of compensation cess. Thereby, delinking aerated beverages from SSBs and removing the extant confusion of taxing aerated beverages under the spirit of SSB taxation.

Tax rates be proportional to the sugar content in the beverages/food items

The international practice, as has been previously discussed, is to tax the SSBs either at a flat rate or at different rates in proportion to the sugar content in the beverages. In line with this global practice, it is suggested that the thumb rule in India for taxing SSBs be “more sugar – more taxes; less sugar-less taxes and no sugar-no taxes.”

The WHO recommends a reduced intake of sugar throughout the life course of an individual. In both adults and children, the WHO recommends reducing the intake of sugar to less than 10% of the total energy intake. As Zero Sugar products contain no sugar, such products should be encouraged by way of a lower tax rate of taxation rather than being discouraged in the form of exorbitantly high rate of taxation and being considered a sin or demerit good.

Clear distinction between beverages containing sugar and sugar free versions

In line with the WHO manual, two important aspects that Indian tax policy makers need to be mindful about are – (a) sugar free versions should not be categorized as SSBs and wherever necessary they can be explicitly excluded as in the examples of US city taxes and (b) sugar containing beverages beyond aerated drinks should be recognized as leviable to the SSB tax in the larger public health interest.

A recommended practice in this regard is to make the tax tariff explicit about the applicable rates to sugared version and sugar free versions of different products. A good example which does this is the tariff of Finland. An illustrative extract of the same is presented in Annexure – C.

Distinction between sugar and artificial sweeteners

Another necessary precaution to be taken in this regard is to address the non-equivalence of artificial sweeteners and sugar. The concern of SSB taxation worldwide is sugar. However, there is a concern that use of artificial sweeteners may contribute to the development of different health conditions including obesity and type 2 diabetes. The recently published WHO meta-analysis and systematic review has flagged such issues and advised for the reduction of these non-sugar sweeteners which are scientifically identified as “low/no calorie sweeteners” (LNCS). The WHO review flags potential harm that these LNCS could cause. [42]

The review has got widespread criticism with the UK’s Office for Health Improvement and Disparities commenting that “the guideline may go too far” and with the Australian government’s Department of Health and Aged Care who wrote that “the recommendation may result in undesirable health outcomes for some individuals.” While the WHO report itself concedes that the “the evidence is ultimately inconclusive”, various countries and health/industry advocacy bodies have contended that public policy recommendations should be developed on the basis of the highest quality, objective and comprehensive evidence which is available.[43]

In India, the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI) responded to it and noted that WHO has classified this guideline on artificial sweeteners as “Conditional”. A “Conditional” recommendation by WHO means that there is a no certainty or a varying degree of certainty about the statement being made. Therefore, it lacks scientific rigour and hence there is a need to show caution that this guideline does not have deleterious effect in India’s public health effort to reduce the consumption of free/added sugars.[44]

It must be noted that various human intervention research studies suggest that the use of artificial sweeteners is either neutral or beneficial for weight management. Artificial sweeteners are not carbohydrates. So unlike sugar, artificial sweeteners don’t raise blood sugar levels. Further, these sweeteners don’t contribute to tooth decay and cavities.[45]

Further, LNCS are safe and have been extensively researched and a proved by safety bodies around the world such as Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA), the US Food and Drug Administration[46] and the European Food Safety Authority.[47]

Research has established that artificial sweeteners have a role to play in the fight against obesity, helping adults and children reduce their calorie intake and body weight, when used instead of sugar, and as part of a varied and balanced diet and a healthy lifestyle.[48]

Beverages sweetened with LNCS have been found to be associated with reduced body weight, body mass index, percentage of body fat, and intrahepatocellular lipid. Therefore, such beverages are a viable replacement strategy in adults with overweight or obesity who are at risk for or have diabetes providing benefits that are similar to those of water, the standard-of-care substitution.[49]

LNCS are also accepted amongst the community of dentists. They have been found to not contribute to tooth decay and its use instead of sugar is recommended on the ground that it actually contributes to the maintenance of tooth mineralisation and to the neutralisation of plaque acids.[50]

The Government of England has advocated for reformulation of products containing free sugar and their advisory recommends – (a) reformulating products to lower the levels of sugar present, (b) reducing the number of calories in, and/or portion size, of products that are likely to be consumed by an individual at one time and (c) shifting consumer purchasing towards lower/no added sugar products.[51] Similarly peer reviewed research considers LNCS as an essential tool in helping food and drink companies reformulate products, to reduce the amount of sugar and calories contained.[52]

Also, such LNCS are widely used in fruit juices and other processed foods, such as, baked goods, breakfast cereals, frozen desserts, candy, puddings, canned foods, jams and jellies and dairy products. The tax on all these products is in the range of 12 – 18%. There is, therefore, no justification in imposing a high tax on beverages containing artificial sweeteners.

Thus, as is the international practice, it is recommended not to tax products with LNCS. If any tax is to be imposed on LNCS sweetened beverages, at the most, the same logic advocated for sugar should be adopted where a tiered tax structure in proportion to the amount of LNCS contained can be adopted.

Rationalize the rate of SSB tax in India

Food items like Gulab Jamun, Jalebi, Malpua and Imarti – which contain high sugar – are charged to GST at 5% only. The GST on sugar is at 5%; on sugar boiled confectionery it is at 12%. Likewise, ice-cream, chocolates, sugar syrup, cakes and pastries attract GST at 18%. Even chewing gums and bubble gums carry a GST of 18% only.

Artificial sweeteners are widely used in fruit juices and other processed foods, such as, baked goods, breakfast cereals, frozen desserts, candy, puddings, canned foods, jams and jellies and dairy products. The GST on fruit juices is 12%. On other goods it is at 12%-18% only. Hence, there is no justification in the extant high tax on Zero Sugar and similar aerated beverages. Therefore, there is an urgent need not only to categorize products as SSBs, appropriately but also to rationalize the tax rate on products identified as SSBs.

Encourage the retail industry to make good of the market gap in beverage industry

The beverage sector constitutes a major vertical of retail for medium and small retailers accounting to nearly 30% of their overall sales, making it a major part of their incomes. These are the local Kirana shops, neighbourhood stores, paan shops and other similar establishments.

Confederation of All India Traders (CAIT) estimates that the beverage industry holds the potential to immediately give a major fillip to retailers’ income, giving them more working capital to leverage. A tiered taxation system pegged to the sugar content in the beverage, translates to lower taxes on beverages with less or no tax. This lesser tax liability opens up capital for the retailers to make more purchases, increase sales and double their incomes.

Given India’s position as the leading producer of milk, sugar, and several fruits, the retail industry can indirectly benefit from the increased engagement of the beverage industry with farmers. To provide a scope for innovation in the industry, it is necessary not to tax the industry harshly but to appreciate the nuances and subtle distinctions. Therefore, taxation should be geared toward renovation and not decimation of the industry and the large number of retailers who could potentially benefit from the industry.

The products from the beverage industry are clubbed with tobacco and alcohol without due appreciation as to how they are not in the same league as these products. A reassessment of this unfortunate categorization is essential. Such categorization alongside tobacco and alcohol adversely impacts the sales of such products from retailers and hampers the revenue inflow to retailers from the industry. Retailers at present sell these products across different age groups of consumers unlike tobacco and alcohol. Identification with such socially taboo products can narrow down the demography of the consumers. Therefore, beverages should not be clubbed with the likes of tobacco, pan masala and alcohol. Rather, they must be a separate category where sugared versions are taxed at a higher rate to discourage their consumption.

Be considerate of the industry and economy level second order effects of taxing SSBs harshly

The higher tax on Zero Sugar and other similar drinks is passed on to the consumers through higher shelf prices. The tax is considered regressive, since the small retailers and consumers on lower incomes are more negatively impacted by higher prices than consumers on higher incomes. Looking from this angle, there is no case for subjecting Zero Sugar and similar products to such a high rate of taxation.

The soft drink companies have investment plans to manufacture zero sugar/zero calorie aerated drinks in India over the next few years. Some of these plans are at a preliminary stage; final decisions are yet to be taken. Reduction in GST on this product to 18% would provide the much-needed impetus for the companies to firm up their investment decisions. Needless to mention, the country needs private investment in a bigger way for the growth and welfare of the people.

THE LONG-TERM GOAL OF A SUGAR BASED TAX (SBT)

In the interest of public health, it is recommended to impose health taxes on sugary foods on par with sugary beverages in the long run. That shall stand aligned with the health goals under the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations and the WHO recommendations on taxing added sugar to curb diseases.[53] This recommendation springs from the understanding of the detrimental health effects of excessive sugar consumption, the equity and fairness of comprehensive taxation, and the need for a multifaceted approach to address health challenges. Such health taxes on both sugary foods and beverages can promote healthier choices, generate revenue for public health initiatives, and contribute to the achievement of the SDG targets related to health and well-being.

Health taxes are levied on goods that adversely affect health such as alcohol, tobacco, SSBs and certain foods (e.g. confectionaries, chocolate, ice creams, salt, fats, etc.). They can be levied directly on the component that creates negative health effects (e.g. alcohol volume, gram of sugar, salt or saturated fat) or on the product that contains the component that is harmful to consumer health (e.g. per litre of soft drink or alcoholic beverage or per pack of cigarettes). They can also be levied when these components or products are used as inputs in the production process.[54] Health taxes make it costlier to consume unhealthy products or to engage in unhealthy behaviour. By doing so, they nudge the public at large to make healthier choices.

In India, the idea of taxing unhealthy foods in the interest of public health is not new. The Niti Aayog hinted at this approach in its annual report last year when it noted – “The incidences of overweight and obesity are increasing among children, adolescents and women in India. A national consultation on the prevention of maternal, adolescent and childhood obesity was organized under the Chairmanship of Member (Health), NITI Aayog, on 24 June 2021 to discuss policy options to tackle the issue. NITI Aayog, in collaboration with IEG and PHFI, is reviewing the evidence available to understand the actions India can take, such as front-of-pack labelling, marketing and advertising of HFSS foods and taxation of foods high in fats, sugar and salt.”[55]

The important reasons that support a sugar-based tax (SBT) which taxes both sugary foods and sugary beverages based on the sugar content in these products are as follows:

- SBT as a tool to achieve SDGs: Excessive sugar consumption poses significant health risks, hindering the achievement of health-related Sustainable Development Goals. Taxing sugary foods on par with sugary beverages fosters a comprehensive approach that aligns with the SDGs. Excessive sugar consumption undermines multiple health-related SDGs, including SDG-3 (Good Health and Well-being), SDG-2 (Zero Hunger), and SDG-12 (Responsible Consumption and Production)[56].

Taxing both sugary foods and beverages contributes to achieving these goals by reducing non-communicable diseases, promoting healthy diets, and fostering sustainable consumption patterns. - SBT as a tax that achieves both Equity and Fairness: Equity should guide taxation policies, ensuring fairness and equal treatment of sources contributing to excessive sugar intake. Taxing sugary foods on par with sugary beverages recognizes their shared role in health outcomes, avoiding a disproportionate burden on specific industries.

- SBT as a comprehensive approach for SDG Integration: A comprehensive approach, encompassing both sugary foods and beverages, aligns with the interconnected nature of the SDGs. Such an approach recognizes the multifaceted drivers of health challenges and aims to address them holistically, contributing to the achievement of multiple SDG targets simultaneously.

- SBT as a tool for Revenue Generation and SDG Financing: Taxation on sugary foods generates additional revenue that can be allocated to SDG financing. These funds can support health systems strengthening, nutrition programs, and access to affordable healthcare, addressing SDG-3. By linking taxation policies with SDG financing, we enhance the sustainability and impact of public health initiatives.

- Collaborative Approach and Stakeholder Engagement: Effective policy implementation requires collaboration between policymakers, public health experts, industry stakeholders, and civil society organizations. Engaging stakeholders fosters shared responsibility and ensures that diverse perspectives contribute to the design and implementation of comprehensive sugar taxation policies.

The WHO and FAO have noted that economic tools (pricing) that favour food products of high nutritional quality and low environmental impact are necessary to bring the practices that compose the global food system in line with achieving Agenda 2030. Sugar products are not a source of food that deserve any favour under this approach. Sustainable diets should be made affordable, and unsustainable diets should be discouraged. In this regard, it has been recommended that a wise employment of taxation tools should align economic incentives with the health and environmental requirements of sustainable diets and discourage the consumption of ultra-processed food products that contain high amounts of sugar, salt and fat.[57]

An SBT levy would be in line with such vision of the WHO and FAO.

CONCLUSION

Beverages are neither a sin category good nor a luxury good. Some of them are unhealthy and reformulating them into healthier versions is the objective of the global movement against SSBs. It is the achievement of that larger goal that tax policy should ideally contribute towards.

The optimal design of an SSB tax will vary between jurisdictions. However, emerging evidence demonstrates some ‘best practice’ principles. Taxes that incentivize industry reformulation are likely to have the greatest impacts. Tiered volume-based and sugar-based excise tax designs appear to be most effective because they can incentive both consumer behaviour change and industry reformulation. Broad-based taxes that raise prices on a wide range of unhealthy food products can minimize scope for substitution of equally (or more) unhealthy untaxed products.[58]

In light of this evidence from global best practice, Indian tax policy makers need to reconsider the current taxation regime of SSBs and take steps to ensure that the SSB taxation design in India satisfies the following three criteria –

- Simplicity of the tax (ease of administration and taxpayer compliance)

- Efficiency of the tax (whether the tax causes desired changes in economic behaviour)

- Equity of the tax (whether the tax treats all applicable products equally).

In line with the WHO guidelines, simplicity of tax design can be achieved by keeping the taxing rule simpler – a higher sugar content attracts higher tax.

For equity criterion to be satisfied the taxable product basket has to be broad enough to include all sugar sweetened beverages from the likes of buttermilk, curdled milk, yoghurt, fermented cream etc which are sweetened with sugar and as such are an equal public health concern. This minimizes the scope for substitution of SSBs with equally (or more) unhealthy untaxed products.

The policy mix approach of complementing SSB taxation with creating public awareness of healthy dietary choices, nutritional labelling, sensitive marketing practices and nudging industry towards reformulation of product offerings to more healthier versions can in the long run ensure efficiency of the SSB tax.

It is hoped that a holistic approach shall be adopted by the policy makers in India to effectively participate in the global efforts to battle obesity and related diseases and to contribute positively to the public health of the country’s population.

In the long run, it is recommended to impose health taxes on sugary foods on par with sugary beverages so as to address the growth of obesity and related diseases. Thus, moving from a SSB tax to a Sugar Based Tax (SBT).

Annexure – A:

Extract from the report on the Revenue Neutral Rate and Structure of Rates for the Goods and Services Tax, 2015

It is now growing international practice to levy sin/demerit rates—in the form of excises outside the scope of the GST–on goods and services that create negative externalities for the economy (for example, carbon taxes, taxes on cars that create environmental pollution, taxes to address health concerns etc.). As currently envisaged, such demerit rates—other than for alcohol and petroleum (for the states) and tobacco and petroleum (for the Centre)—will have to be provided for within the structure of the GST. The foregone flexibility for the center and the states is balanced by the greater scrutiny that will be required because such taxes have to be done within the GST context and hence subject to discussions in the GST Council.

We recommend one demerit rate and that rate should be such that the current revenues from that high rate are preserved. Accordingly, we recommend that this sin/demerit rate be fixed at about 40 percent (Centre plus States) and apply to luxury cars, aerated beverages, paan masala, and tobacco and tobacco products (for the states). The Centre can, of course, levy an additional excise on tobacco and tobacco products over and above this high rate. These goods are final consumer goods and should be of high value (so that small retail outlets are not burdened with the complication of having to deal with multiple rates) and clearly identifiable so that there are no issues related to classification that could complicate tax compliance.

(emphasis supplied)

Annexure – B:

Extract of Tariff from Indian GST

Notification No. 1/2017 – Central Tax (Rate) dated 28.06.2017.

| S No. | Chapter / Heading / Subheading / Tariff item | Description of Goods | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Schedule – II – 6% (CGST) + 6% (SGST) | |||

| 2202 90 10 | Soya milk drinks | 12% | |

| 2202 90 20 | Fruit pulp or fruit juice based drinks | 12% | |

| 2202 90 30 | Beverages containing milk | 12% | |

| 2202 90 90 | Tender coconut water put up in unit container and bearing a registered brand name | 12% | |

| Schedule – IV – 14% (CGST) + 14% (SGST) | |||

| 11 | 2202 90 90 | Other non-alcoholic beverages | 28% |

| 12 | 2202 10 | All goods [including aerated waters], containing added sugar or other sweetening matter or flavoured | 28% |

Notification No. 1/2017 – Compensation Cess (Rate) dated 28.06.2017, as amended till date

| S No. | Chapter / Heading / Subheading / Tariff item | Description of Goods | Rate of goods and services tax compensation cess |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| 2 | 2202 10 10 | Aerated waters | 12% |

| 3 | 2202 10 20 | Lemonade | 12% |

| 4 | 2202 10 90 | Others | 12% |

| 4A | 2202 99 90 | Caffeinated Beverages | 12% |

| 4B | 2202 | Carbonated Beverages of Fruit Drink or Carbonated Beverages with Fruit Juice | 12% |

Annexure C:

Extract of Tariff from Finland’s Excise Tax

| Heading | Description | Tax Rate |

| 2201 | Waters, including natural or artificial mineral waters and aerated waters, not containing added sugar or other sweetening matter nor flavoured; ice and snow | 11.0 cent/l |

| 2202

|

Waters, including mineral waters and aerated waters, containing added sugar or other sweetening matter or flavoured, and other non-alcoholic beverages, not including fruit or vegetable juices of heading 2009 (of an alcoholic strength by volume of 0.5% vol. or less) | 22.0 cent/l |

| – sugar free | 11.0 cent/l | |

| 2206

|

Other fermented beverages (for example, cider, perry, mead); mixtures of fermented beverages and mixtures of fermented beverages and non-alcoholic beverages, not elsewhere specified or included (of an alcoholic strength by volume in excess of 0.5% vol.) | |

| – of an alcoholic strength by volume of 1.2% vol. or less, excluding mixtures of beer and non-alcoholic beverages | 22.0 cent/l | |

| – sugar free | 11.0 cent/l |

(emphasis supplied)

Source: Taxes in Europe Database – Finland, Version date – 17 Feb 2015 https://ec.europa.eu/taxation-customs/tedb/legacy/taxDetail.html;jsessionid=roEK10UYwGaCjGQ1vvMM-T7u48Pd7Qpjq7g2Q26mcxGqEgY1zi-9!-1656329434?id=2001/1424159141&taxType=Other%20indirect%20tax

Annexure – D:

Details of SSB Tax in different taxation jurisdictions across the globe

| NO | Country | Implementation Date | Amount of Tax | Products Subject to the Tax | Policy instrument (e.g. excise tax, ad valorem tax) | Additional Notes |

| 1 | Bahrain | Dec-17 | 100% tax rate on energy drinks 50% tax rate on soft drinks |

Soft drinks: any aerated beverage except unflavoured aerated water and include any concentrates, powder, gel or extracts intended to be made in to an aerated beverage. |

Excise tax | |

| 2 | Barbados | 01-Aug-15 | 10% | Locally produced and imported sugary drinks, including carbonated soft drinks, juice drinks, sports drinks and others. |

Excise tax | Exempt: 100% natural fruit juice, coconut water, plain milk and evaporated milk. |

| 3 | Belgium (1/2) | 01-Jan-16 | €0.068 (around $0.07) per litre |

All soft drinks, including non-alcoholic drinks and water containing added sugar or other sweeteners or flavours. |

Excise tax | |

| 4 | Belgium (2/2) | 01-Jan-16 | €0.41 per litre (around $0.45) and €0.68 per kg (around $0.70) |

Any substance intended for the use of manufacturing soft drinks (values for liquid and powder, respectively). |

Excise tax | |

| 5 | Brunei | 01-Apr-17 | 0.40 Brunei dollars/litre (around $0.28) |

1. SSBs with more than 6gm/100mL total sugar 2. Soy milk drinks with >7gm/100mL total sugar 3. Malted or chocolate drinks with >8gm/100mL total sugar 4. Coffee based or flavoured drinks with ≥6gm/100mL. |

Excise tax | Exempt: Milk-based drinks and fruit juices are exempt from the tax. |

| 6 | Chile (1/2) | 01-Jan-15 | 18% | Sugary drinks with >6.25gm/100ml of sugar. Includes all non-alcoholic drinks with added sweeteners including energy drinks and waters. | Ad valorem tax | |

| 7 | Chile (2/2) | 01-Jan-15 | 10% | Sugary drinks with <6.25gm/100mL of sugar | Ad valorem tax | |

| 8 | Dominican Republic |

1 September 2015 |

10% | Soft drinks and other sweetened drinks (including energy drinks). |

Excise tax | This tax also applies to foods with high sugar content. |

| 9 | Fiji (1/2) | Aug-17 | 35 cents/litre (around $0.17) |

Locally produced sweetened beverages including carbonated and non-carbonated drinks sweetened with sugar or artificial sweeteners | Excise tax | Tax revenue goes to a general fund and aims to protect children from obesity and lifelong poor health. |

| 10 | Fiji (2/2) | Aug-17 | 15% & 10% | Imported sweetened beverages and imported powders, preparations used to make beverages (other than milk-based drinks) (15%). Flavoured and coloured sugar syrups (10%). | Ad valorem tax | |

| 11 | Finland | 2014 | €0.220/litre and €0.11/litre |

Beverages with >0.5% sugar and other non-alcoholic beverages, respectively | Excise tax | Producers with annual production volume <50000 litres are exempted from the tax. The €0.95/kg by weight tax for confectionary and ice cream was removed 1 January 2017. |

| 12 | France | 01-Jan-12 | €0.11/1.5 litres | Drinks with added sugar and artificial sweeteners, including sodas, fruit drinks, flavoured waters and ‘light’ drinks | Excise tax | Revenue used for the general budget. |

| 13 | French Polynesia |

2002 | 40 CFP franc/litre (around $0.44) and 60 CFP franc/litre (around $0.68) |

Sweetened drinks, domestically produced and imported, respectively. | Excise tax | Between 2002 and 2006, tax revenue went to a preventive health fund; from 2006, 80% has been allocated to the general budget and earmarked for health. |

| 14 | Hungary | Sep-11 | 7 forints/litre (around $0.024), and 200 forints/litre (around $0.70) |

Soft drinks and concentrated syrups used to sweeten drinks, respectively. | Excise tax | This is a ‘public health tax,’ applied also to salt and caffeine content of various categories of sugar sweetened pre-packaged, ready to-eat foods, and salty snacks. |

| 15 | India | 01-Jul-17 | 28% + 12% cess (tax upon a tax) |

Includes aerated waters and drinks containing added sugar or other sweetening matter or flavour | GST | Applied across India, this tax replaces all other GST laws at State level. It applies to sweetened foods and is the highest GST rate for goods in India. |

| 16 | Ireland | 01-May-18 | 20 cents/litre for drinks with between ≥5gm/100mL and 8gm/100mL. 30 cents/100mL for drinks with >8gm/100mL |

Non-alcoholic, water-based drinks | Excise tax | Exempt: Fruit juices and dairy products |

| 17 | Kiribati | 2014 | 40% | Non-alcoholic beverages, including mineral and aerated waters that contain added sugar, other sweeteners or flavourings | Excise tax | Exempt: Fruit and vegetable juices as well as fruit concentrates. |

| 18 | Mauritius | Oct-16 | 0.03 rupees/gm sugar (around $0.0008) |

All SSBs, imported or locally produced, including juices, milk-based beverages and soft drinks. | Excise tax | The previous tax (since 1 January 2013) was only applied to the sugar content of soft drinks. |

| 19 | Mexico (1/2) | 01-Jan-14 | 1 peso/litre (around $0.05, or 10%) |

All drinks with added sugar | Excise duty | Exempt: Milks and yoghurt drinks. Revenue is currently being allocated to the general budget but should be allocated to programmes addressing malnutrition, obesity and obesity-related chronic diseases, as well as access to drinking water). An ad valorem excise duty of 8% also applies to food with high calorie density ≥275 kcals/100gm. |

| 20 | Mexico (2/2) | 01-Jan-11 | 25% | Energy drinks, defined as non-alcoholic beverages with >20mg/100Ml of caffeine and mixed with stimulants (eg. Taurine). It also applies to concentrates, powders and syrups used to prepare energy drinks. |

Special tax on production and services law |

|

| 21 | Nepal | 2002 | Rs.11/L on fruit and vegetable juices, whether or not containing added sugar or other sweetening matter (HS 2009); Rs. 50/L on energy drinks (HS 2202.99.10); Rs. 14/L on other SSB under HS 2202.99.90; Rs. 20/L on non-alcoholic beer (2202.91.00) | SSB under HS 2009, 2202, 1806, 2106 | Excise tax | |

| 22 | Norway | 2017 | 3.34 NOK/litre (around $0.40) and 20.32 NOK/litre (around$2.44) |

Non-alcoholic beverages containing added sugar or sweeteners and concentrated syrups, respectively. | Excise tax | Tax originally implemented in 1981. |

| 23 | Palau | Sep-03 | $0.28175/litre | Carbonated soft drinks | Import tax | |

| 24 | Peru | 10-May-18 | 25% on beverages with ≥6gm/100ml |

Includes non-alcoholic beverages, sweetened waters and 0% alcohol beer | Excise tax | Exempt: Beverages <6gm/100ml sugar content |

| 25 | Philippines (1/2) |

01-Jan-18 | 6 pesos/litre (around $0.12) |

On sweetened beverages using purely caloric and purely non-caloric sweeteners or a mix of both. | Excise tax | |

| 26 | Philippines (2/2) |

01-Jan-18 | 12 pesos/litre (around $0.24) |

Drinks using purely high-fructose corn syrup in combination with above sweeteners. Beverages for both taxes include juice drinks, tea, carbonated beverages, flavoured water, energy and sports drinks, powdered drinks not classified as milk, juice, tea and coffee, cereal and grain beverages | Excise tax | Exempt: 100% natural fruit and vegetable juices, milk products, meal replacement and medically indicated beverages. |

| 27 | Poland | 2021 | PLN 0.50 per L base fee; Additional PLN 0.05 per gram sugar >5g/100ml; Additional PLN 0.09 per L on drinks containing caffeine or taurine; Total soda fee cannot exceed PLN 1.2 per L; Juice drinks with >20% juice content and isotonic sports drinks with >5g sugar/100mL not charged base fee of PLN 0.5 per L. | Non-alcoholic drinks containing added sugar or artificial sweeteners, caffeine or taurine containing sugar > 5g/100 ml | Excise tax | Exempt: Sports/isotonic drinks with sugar content ≤5g sugar/100mL, juice products with content of no less than 20 per cent of fruit or vegetable juice with max. sugar content of 5 g/100 ml, and beverages with milk or milk products as the first/primary ingredient |

| 28 | Portugal | 01-Feb-17 | €0.08 (around $0.10) for drinks with <80g/litre, or €0.16 (around $0.20) for drinks >80gm/litre. |

Mineral, flavoured and aerated waters containing added sugar or sweeteners. | Excise tax | |

| 29 | St Helena | 27-May-14 | ₤0.75/litre (around $0.95) |

High sugar carbonated drinks defined as drinks containing ≥15g/litre sugar. | Excise tax | |

| 30 | Samoa | 2008 | 0.4 Tala/litre (around $0.17) |

Soft drinks, both imported and locally produced. | Excise tax | Soft drinks have been taxed in Samoa since 1984. |

| 31 | Saudi Arabia | 09-Jun-17 | 100% and 50% | Energy drinks and carbonated drinks (soft drinks, carbonated water and juice), respectively. | Excise tax | The rates may differ depending on the product. For example, carbonated drinks may have different tax rate if they are dispensed as fountain drinks or as cans. |

| 32 | South Africa | Apr-18 | 2.1 cents ($0.17)/gm sugar |

Sugary beverages (mineral and aerated waters containing added sugar or other sweeteners or flavours and other non alcoholic beverages) that contain >4gm/100mL. | Sugary beverages levy |

Exempt: Fruit and vegetable juices. Also, drinks <4gm /100mL sugar content. |

| 33 | Spain (Catalonia region only) |

01-May-17 | €0.08/litre (around $0.10) price increase for drinks with 5- 8gm/100ml sugar and €0.12/litre for drinks with >8gm/100ml |

Packaged sugary drinks: Soft drinks, flavoured water, chocolate drinks, sports drinks, cold tea and coffee drinks, energy drinks, fruit nectar drinks, vegetable drinks, sweetened milk, alternative milk drinks, milkshakes and milk drinks with fruit juice. |

Sugary drink levy | Exempt: Natural fruit juices, alcoholic beverages, sugar-free soft drinks and alternatives to milk with no added caloric sweeteners |

| 34 | Thailand (1/2) |

16 September 2017 |

Drinks containing: 6-8gm/100mL – 0.10 baht/litre (around $0.0031) 8-10gm/100mL – 0.30 baht/litre (around $0.0095) 10-14gm/100mL – 0.50 baht/litre (around $0.015) >14g/100mL – 1 baht (around $0.031) |

Added to the above drinks | Excise tax | The sugar tax will increase every two years. From 2023 onwards the tax will be 6-8gm/100mL – 1 baht/litre (around $0.031) 8-10gm/100mL – 3 baht/litre (around $0.095) >10gm/100mL – 5 baht/litre (around $0.15) |

| 35 | Thailand (2/2) |

16 September 2017 |

14% and 10% | Artificial mineral water, soda water, carbonated soft drinks without sugar or other sweeteners and without flavour, mineral water and carbonated soft drinks with added sugar or other sweeteners or flavours (14%) and fruit and vegetable juices (10%) |

Ad valorem tax | |

| 36 | Tonga | 2013 | 1 Pa’anga/litre (around $0.050) |

Soft drinks containing sugar or sweeteners | Excise tax | |

| 37 | United Arab Emirates (UAE) |

01-Oct-17 | 50% and 100% | Carbonated (aerated beverages and concentrations, powders, gel or extracts for production of aerated beverages) and energy drinks (marked or sold as an energy drink or contains stimulant substances), respectively. |

Excise tax | The excise tax applies to the import, manufacturing, stockpiling or release of excisable goods. |

| 38 | United Kingdom (UK) | 01-Apr-2018 | Any pre-packaged soft drink with added sugar containing at least 5gm of total sugars/100mL, ≥produced and packaged in the UK and soft drinks imported into the UK: 5-8gm/100mL – ₤0.18/litre ($0.25) >8gm/100mL – ₤0.24/litre ($0.34) |

Soft drinks levy | Exempt: Milk-based drinks, milk substitute drinks, pure fruit juices or any other drinks with no added sugar, alcohol substitue drinks and soft drinks of a specified description which are for medicinal or other specified purposes.

Brighton & Hove Council is promoting a voluntary sugar tax for food outlets. Money raised from a voluntary ₤.10 levy (around $0.15) on all non-alcoholic SSBs sold will go to the Children’s Health Fund, set up by Sustain: the Alliance for Food and Farming in Partnership with Jamie Oliver in 2015. It will Contribute to the Support of food Education and health initiatives for children. |

|

| 39 | United States – city of Berkeley, California | 15 March 2023 | 1 cent/ounce | Applies to soda, energy drinks and heavily pre-sweetened tea as well as caloric sweeteners used to produce them. | Excise tax | Exempt: Infant formula, milk products, and natural fruit and vegetable juices.

The revenue goes into the City’s general funds for community health and nutrition programmes. |

| 40 | United States – Navajo Nation (spans portions of Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico) | 01 Apr 2015 | 2% tax | SSBs | Excise tax | This tax is on ‘minimal-to-no nutritional value food items,’ including pre-packaged and non pre-packaged snacks including sweets, chips and crisps.The revenue is earmarked for projects such as farming, vegetable gardens, greenhouses, farmers’ markets, healthy convenience stores, clean water, exercise equipment and health classes, all part of the Community Wellness Development Projects Fund. |

| 41 | United States – city of Albany, California | 01 Apr 2017 | 1 cent/ounce | Includes soda, energy drinks, and heavily sweetened tea, as well as added caloric sweeteners used to produce the drinks | Excise | Exempt: Infant formula, milk products, natural fruit and vegetable juices. |

| 42 | United States – city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | 01 Jan 2017 | 1.5 cents/ounce | Any non-alcoholic beverage with caloric sugar-based sweetener or artificial sugar substitute listed as an ingredient, including soda, non-100% fruit drinks, sports drinks, flavoured water, energy drinks, pre sweetened coffee or tea and non-alcoholic beverages intended to be mixed into an alcoholic drink. Also, syrups or other concentrates used in beverages. | Excise tax | Any non-alcoholic beverage with caloric sugar-based sweetener or artificial sugar substitute listed as an ingredient, including soda, non-100% fruit drinks, sports drinks, flavoured water, energy drinks, pre sweetened coffee or tea and non-alcoholic beverages intended to be mixed into an alcoholic drink. Also, syrups or other concentrates used in beverages. |

| 43 | United States – city of Boulder, Colorado | 01 July 2017 | 2 cents/ounce | SSB defined as any non-alcoholic beverage which contains at least 5gm/12 fluid ounces | Excise tax | Exempt: Any milk product, infant formula, alcoholic beverage or beverage for medical use. Also, any distribution of syrups and powders sold directly to a consumer intended for personal use.

The revenue will be spent on health promotion, wellness |

| 44 | United States – city of Oakland, California | 01 July 2017 | 1 cent/ounce | Defined as any beverage to which one or more caloric sweeteners have been added and that contain ≥kcals/12 fluid ounces of beverage and include sodas, sports drinks, sweetened teas and energy drinks. |

Excise tax | Exempt: Milk products, 100% fruit juice, infant or baby formula, diet drinks or drinks taken for medical reasons.Revenue will be used for any lawful government purpose. |

| 45 | United States – city of Seattle, Washington | 01 Jan 2018 | 1.75cents/ounce of SSB + 1 cent/ounce for manufacturers with a worldwide gross income of >$2,000,000 but <$5,000,000. |

Beverages with caloric sweeteners and the syrups and powders used to prepare them, including sodas, energy drinks, fruit drinks, sweetened teas and ready-to-drink coffee drinks. | Excise tax | Exempt: Drinks with <40kcals/12ounce serving, beverages with milk as the principle ingredient, 100% natural fruit and vegetable juice, meal replacement beverages, infant formula and concentrates used in combination with other ingredients to create a beverage. |

| 46 | United States – city of San Francisco, California | 01 Jan 2018 | 1 cent/ounce | Applies to any SSB containing added sugar and >25kcals/12 ounces. The tax also applies to syrups and powders that can be made into SSBs. |

Excise tax | Exempt: 100% fruit juice, artificially-sweetened beverages, infant formula, and milk products are exempt from tax. Revenue goes into the City’s General Fund. |

| 47 | Vanuatu | 09 Feb 2015 | 50 vatu (around $0.47)/litre | Applied to carbonated beverages containing added sugar or other sweetening matter including mineral waters and aerated waters, containing added sugar or other sweetening matter or flavoured. | Excise tax | |

| Source: World Cancer Research Fund International. Nourishing framework examples of food taxes and subsidies tables. 2018; Websites of revenue administrations of respective countries | ||||||

| https://www.wcrf.org/int/policy/nourishing-database | ||||||

Footnotes

[1] WHO Manual on Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Taxation Policies to Promote Healthy Diets, 2022

[2] Taxes on Sugar Sweetened Beverages: International Evidence and Experiences, September 2020, World Bank

[3] Troen et al. (2023), Israel decides to cancel sweetened beverage tax in setback to public health, The Lancet, 40:10376, P553-554.

[4] ‘Best buys’ and other recommended interventions for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259232/WHO-NMH-NVI-17.9-eng.pdf

[5] Oliver, K., Lorenc, T., Tinkler, J., & Bonell, C. (2019). Understanding the unintended consequences of public health policies: the views of policymakers and evaluators. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1-9.

[6] Draft action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013–2020, WHO, 6 May 2013, https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA66/A66_9-en.pdf

[7] Global Action Plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases, 2013-20, https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/94384/9789241506236_eng.pdf

[8] ‘Best buys’ and other recommended interventions for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259232/WHO-NMH-NVI-17.9-eng.pdf

[9] WHO Manual on Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Taxation Policies to Promote Healthy Diets, 2022

[10] WHO Nutrient Profile Model for South-East Asia Region. To implement the set of recommendations on

the marketing of foods and non-alcoholic beverages to children, 2017; WHO Manual on Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Taxation Policies to Promote Healthy Diets, 2022

[11] Source: Policy Brief: Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Taxation, UNICEF

[12] Flanagan, Kieron, Elvira Uyarra, and Manuel Laranja. “Reconceptualising the ‘policy mix’for innovation.” Research policy 40.5 (2011): 702-713.

[13] Mavrot, Céline, Susanne Hadorn, and Fritz Sager. “Mapping the mix: Linking instruments, settings and target groups in the study of policy mixes.” Research policy 48.10 (2019): 103614.

[14] Taxes on Sugar Sweetened Beverages: International Evidence and Experiences, September 2020, World Bank

[15] WHO Manual on Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Taxation Policies to Promote Healthy Diets, 2022

[16] Hattersley L, Mandeville KL. Global Coverage and Design of Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Taxes. JAMA Network Open. 2023;6(3):e231412. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.1412

[17] Thow, A. M., C. Quested, L. Juventin, R. Kun, A. N. Khan, and B. Swinburn. 2011. “Taxing Soft Drinks in the Pacific: Implementation Lessons for Improving Health.” Health Promot Int. 26:55–64

[18] James, E., M. Lajous, and M. R. Reich. 2019. “The Politics of Taxes for Health: An Analysis of the Passage of the Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Tax in Mexico.” Health Systems & Reform 6 (1): e1669122; WCRF (World Cancer Research Fund International). 2018. Building Momentum: Lessons on Implementing a Robust Sugar Sweetened Beverage Tax. WCRF. www.wcrf.org/buildingmomentum

[19] Hattersley L, Mandeville KL. Global Coverage and Design of Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Taxes. JAMA Network Open. 2023;6(3):e231412. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.1412

[20] Soft Drinks Industry Levy, His Majesty’s Revenue and Customs, https://www.gov.uk/guidance/check-if-your-drink-is-liable-for-the-soft-drinks-industry-levy

[21] Taxes in Europe Database – Finland, Version date – 17 Feb 2015 https://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/tedb/legacy/taxDetail.html;jsessionid=roEK10UYwGaCjGQ1vvMM-T7u48Pd7Qpjq7g2Q26mcxGqEgY1zi-9!-1656329434?id=2001/1424159141&taxType=Other%20indirect%20tax

[22] Sugar Sweetened Drinks Tax (SSDT), Irish Tax and Customs,

[23] INFORMATION CIRCULAR (RAA-SSB updated 2023-01-03) ISSUED: March 17, 2022, Department of Finance, Tax and Fiscal Policy Branch, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador.

[24] Capacci S, Allais O, Bonnet C, Mazzocchi M. The impact of the French soda tax on prices and purchases. An ex post evaluation. PLoS One. 2019 Oct 11;14(10):e0223196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223196. PMID: 31603901; PMCID: PMC6788734.

[25] Giles et al 2019, Case study: The Hungarian public health product tax, UK Health Forum, https://ukhealthforum.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Hungary.pdf

[26] Salgado Hernández, J.C., Ng, S.W. & Colchero, M.A. Changes in sugar-sweetened beverage purchases across the price distribution after the implementation of a tax in Mexico: a before-and-after analysis. BMC Public Health 23, 265 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15041-y

[27] Taxes in Europe Database – Belgium, Version date – 17 Feb 2015 https://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/tedb/legacy/taxDetail.html?id=32/1424158940&taxType=Other+indirect+tax

[28] Sugar Sweetened Beverages Tax, City of Albany, https://www.albanycs.org/departments/finance/sugar-sweetened-beverag-tax

[29] Falbe J, Grummon AH, Rojas N, Ryan-Ibarra S, Silver LD, Madsen KA. Implementation of the First US Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Tax in Berkeley, CA, 2015-2019. Am J Public Health. 2020 Sep;110(9):1429-1437. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305795. Epub 2020 Jul 16. PMID: 32673112; PMCID: PMC7427219.

[30] John Cawley, David Frisvold, Anna Hill, David Jones, Oakland’s sugar-sweetened beverage tax: Impacts on prices, purchases and consumption by adults and children, Economics & Human Biology, Volume 37, 2020, 100865, https://doi-org/10.1016/j.ehb.2020.100865

[31] Treasurer and Tax Collector, San Franciso, https://sftreasurer.org/business/taxes-fees/sugary-drinks-tax

[32] City of Seattle, SSB Tax, https://www.seattle.gov/documents/Departments/SweetenedBeverageTaxCommAdvisoryBoard/FactSheets/SweetenedBeverageTax_FactSheet_2019.pdf

[33] Can We Tax Unhealthy Habits Away? University of Southern California, Spring 2020, https://news.usc.edu/trojan-family/do-sin-taxes-works-usc-experts-in-policy-health-economics-explain/; Do ‘Sin Taxes’ Really Change Consumer Behavior? Knowledge at Wharton, Feb 2017, https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/podcast/knowledge-at-wharton-podcast/do-sin-taxes-really-change-consumer-behavior/

[34] Sin taxes can cost poor families up to ten times more than they cost the wealthy, Institute of Economic Affairs, UK, July 2018, https://iea.org.uk/media/sin-taxes-can-cost-poor-families-up-to-ten-times-more-than-they-cost-the-wealthy/

[35] Kurz CF, König AN. The causal impact of sugar taxes on soft drink sales: evidence from France and Hungary. Eur J Health Econ. 2021 Aug;22(6):905-915. doi: 10.1007/s10198-021-01297-x. Epub 2021 Apr 1. PMID: 33792852; ECSIP Consortium, 2014

[36] Para 5.55 of the Report on the Revenue Neutral Rate and Structure of Rates for the Goods and Services Tax, Government of India, Dec 2015 – Detailed reproduction of relevant extract in Annexure – A

[37] Notification 1/2018-Central Tax (Rate) dated 28.06.2017 read with Notification 1/2018-Compensation Cess (Rate) dated 28.06.2017. Extracts of the corresponding entries from the notifications are in Annexure – B

[38] Schoppen, Stefanie, Ana M. Perez-Granados, Angeles Carbajal, Pilar Oubiña, Francisco J. Sánchez-Muniz, Juan A. Gómez-Gerique, and M. Pilar Vaquero. “A sodium-rich carbonated mineral water reduces cardiovascular risk in postmenopausal women.” The Journal of Nutrition 134, no. 5 (2004): 1058-1063.

[39] Cuomo, Rosario, Raffella Grasso, Giovanni Sarnelli, Gaetano Capuano, Emanuele Nicolai, Gerardo Nardone, Domenico Pomponi, Gabriele Budillon, and Enzo Ierardi. “Effects of carbonated water on functional dyspepsia and constipation.” European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology 14, no. 9 (2002): 991-999.

[40] Cuomo R, Sarnelli G, Savarese MF, Buyckx M. Carbonated beverages and gastrointestinal system: Between myth and reality. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2009; 19(10): 683-9. DOI: 10.1016/j.numecd.2009.03.020; Sørensen LB, Møller P, Flint A, Martens M, Raben A. Effect of sensory perception of foods on appetite and food intake: A review of studies on humans. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2003; 27(10): 1152-66. DOI:10.1038/sj.ijo.0802391

[41] FDA, Code of Federal Regulations Title 21

[42] Leyvraz and Montez, Health effects of the use of non-sugar sweeteners: A systematic review and meta-analysis, World Health Organization, 2023

[43] Results of the public consultation on the WHO draft guideline on use of non-sugar sweeteners, https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/nutritionlibrary/nugag/diet-and-health/nugag-dietandhealth-public-consultation-comments-responses-nss.pdf?sfvrsn=5bdeb24b-3

[44] FICCI Response on WHO Guideline on Use of Non-Sugar Sweeteners, July 2023

[45] Johnston, Craig A., and John P. Foreyt. “Robust scientific evidence demonstrates benefits of artificial sweeteners.” Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism 25, no. 1 (2014): 1.

[46] High-intensity sweeteners https://www.fda.gov/food/food-additives-petitions/high-intensity-sweeteners

[47] Sweeteners https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/sweeteners

[48] Rogers, P.J., Appleton, K.M. The effects of low-calorie sweeteners on energy intake and body weight: a systematic review and meta-analyses of sustained intervention studies. Int J Obes 45, 464–478 (2021). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41366-020-00704-2; Laviada-Molina, Hugo, Fernanda Molina-Segui, Giordano Pérez-Gaxiola, Carlos Cuello-García, Ruy Arjona-Villicaña, Alan Espinosa-Marrón, and Raigam Jafet Martinez-Portilla. ‘Effects of Nonnutritive Sweeteners on Body Weight and BMI in Diverse Clinical Contexts: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis’. Obesity Reviews 21, no. 7 (2020): e13020. doi:10.1111/obr.13020

[49] McGlynn ND, Khan TA, Wang L, et al. Association of Low- and No-Calorie Sweetened Beverages as a Replacement for Sugar-Sweetened Beverages With Body Weight and Cardiometabolic Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(3):e222092. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.2092

[50] Sugar Substitutes and their Role in Caries prevention, Adopted by FDI World Dental Federation General Assembly September, 2008 in Stockholm, Sweden; Commission Regulation (EU) No 432/2012 of 16 May 2012 establishing a list of permitted health claims made on foods, other than those referring to the reduction of disease risk and to children’s development and health, Special edition in Croatian: Chapter 13 Volume 043 P. 281 – 320, 2012; Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to intense sweeteners, EFSA Journal 2011;9(6): 2229.

[51] Public Health England, Sugar Reduction and Wider Reformulation Programme: Stakeholder engagement: May 2016 to March 2017, March 2017; Public Health England, Sugar Reduction: Achieving the 20%: A technical report outlining progress to date, guidelines for industry, 2015 baseline levels in key foods and next steps, March 2017

[52] Ashwell, M., Gibson, S., Bellisle, F., Buttriss, J., Drewnowski, A., et al (2020). Expert consensus on low-calorie sweeteners: Facts, research gaps and suggested actions. Nutrition Research Reviews, 33(1), 145-154. doi:10.1017/S0954422419000283; 1. Gibson S, Ashwell M, Arthur J, et al. What can the food and drink industry do to help achieve the 5% free sugars goal? Perspectives in Public Health. 2017;137(4):237-247. doi:10.1177/1757913917703419

[53] WHO and Sustainable Development Goals, https://www.who.int/europe/about-us/our-work/sustainable-development-goals

[54] Health Taxes: Policy and Practice, 2022 World Health Organization (WHO)

[55] Annual Report 2021-22, Niti Aayog, Government of India; https://health.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/policy/niti-studying-proposal-to-tax-foods-high-in-sugar-salt-to-tackle-obesity/89871903

[56] Sustainable Development Goals, https://sdgs.un.org/goals

[57] HLPE. 2020. Food security and nutrition: building a global narrative towards 2030. A report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security, Rome.

[58] Taxes on Sugar Sweetened Beverages: International Evidence and Experiences, September 2020, World Bank

A PDF version of the report is available here.

©Creative Commons Licence, 2023

Designed by: Shriya Bhatia, Lead Graphic Designer, DeepStrat